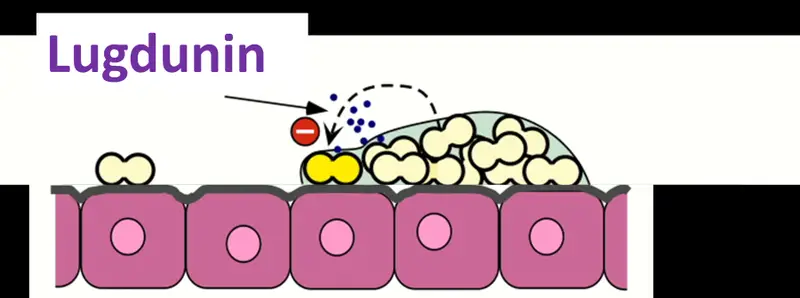

A potential lifesaver lies unrecognised in the human body. Scientists at the University of Tübingen and the German Centre for Infection Research (DZIF) have discovered that Staphylococcus lugdunensis (which colonises inside the human nose) produces a previously unknown antibiotic. As tests on mice have shown, the substance which has been named Lugdunin is able to combat multi-resistant pathogens, where many classic antibiotics have become ineffective. The study results were published on 27th July in the peer-reviewed journal Nature.

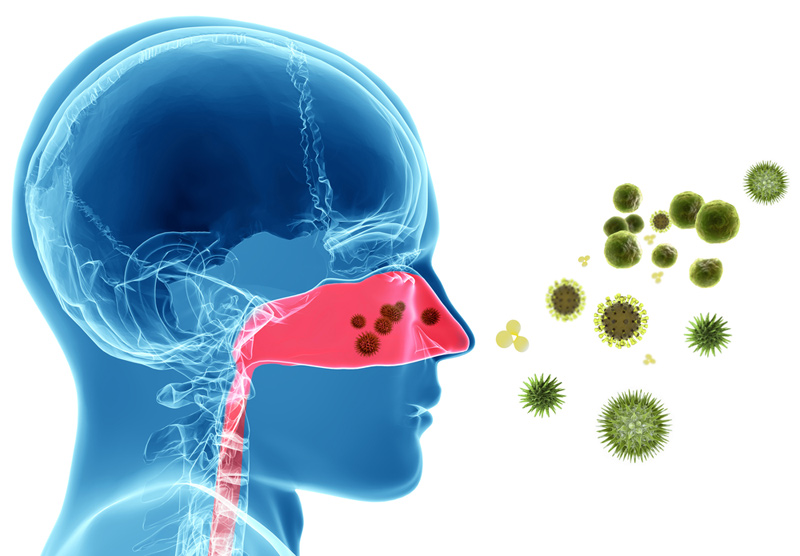

Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria – like the pathogen Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) which colonises on human skin – are among the leading causes of death worldwide. The natural habitat of harmful Staphylococcus bacteria is the human nasal cavity. In their experiments, Dr. Bernhard Krismer, Alexander Zipperer and Professor Andreas Peschel from the Interfaculty Institute for Microbiology and Infection Medicine Tübingen (IMIT) observed that Staphylococcus aureus is rarely found when Staphylococcus lugdunensis is present in the nose.

"Normally, antibiotics are formed only by soil bacteria and fungi," explains Professor Andreas Peschel. "The notion that human microflora may also be a source of antimicrobial agents is a new discovery." In future studies, researchers will examine whether Lugdunin could actually be used in therapy. One potential use is introducing harmless Lugdunin-forming bacteria to patients at risk from MRSA as a preventative measure.

Staphylococcus lugdunensis (white) colonise on human nasal epithelial cells (pink) and combat the Staphylococcus aureus pathogen (yellow) by producing Lugdunin. Graphic: Professor Andreas Peschel. Staphylococcus lugdunensis (white) colonise on human nasal epithelial cells (pink) and combat the Staphylococcus aureus pathogen (yellow) by producing Lugdunin. Graphic: Professor Andreas Peschel. |

Researchers from the Institute of Organic Chemistry at the University of Tübingen closely examined the structure of Lugdunin, noting that it consists of a previously unknown ring structure of protein blocks and thus establishes a new class of materials.

Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem worldwide. "There are estimates which suggest that more people will die from resistant bacteria in the coming decades than cancer," says Dr. Bernhard Krismer. "The improper use of antibiotics strengthens this alarming development" he continues.

As many of the pathogens are part of human microflora on skin and mucous membranes, they cannot be avoided. Particularly for patients with serious underlying illnesses and weakened immune systems they are a high risk – these patients are easy prey for the pathogens. Now the findings made by scientists at the University of Tübingen open up new ways to develop sustainable strategies for infection prevention and to find new antibiotics – also in the human body.

"If we can understand why they are living there [the nose] we may find new ways to combat bad bacteria, eradicate the spread of infection and maybe even find new therapeutic concepts, because we are in desperate need for new antibiotics," he concludes.